Hélène Bresslau Schweitzer: The Woman Who Built a Hospital, Then Vanished from History

The sun beat down on the riverbank at Lambaréné.

Sheets hung between wooden posts, catching the wind like sails. A woman bent over a basin of water, scrubbing away the red dust of the forest. Her sleeves were rolled up, her face pale beneath the African sun, her movements steady and sure. Inside a nearby chapel, an organ played — the familiar sound of Bach echoing across the jungle.

The music came from Albert Schweitzer, the man the world would celebrate.

But the hands that built his dream belonged to Hélène, the woman history nearly forgot.

The Woman Behind the Legend

Albert Schweitzer — theologian, musician, doctor, philosopher, and Nobel Peace Prize laureate — became a symbol of humanitarian devotion. Yet behind his legacy stood a woman who made it possible.

Hélène Bresslau Schweitzer wasn’t his assistant.

She was his equal in courage, intellect, and vision.

Born in Berlin in 1879 to a Jewish family that had converted to Protestantism, Hélène grew up in a world that expected women to be quiet, domestic, and obedient. She refused all three.

She studied pedagogy and sociology, earned a teaching certificate, and spoke multiple languages. She worked in England and Russia, eager to understand how people lived and learned across cultures. In Strasbourg, she served as an inspector of orphanages — a demanding role few women held at the time.

In 1907, long before anyone spoke of “women’s empowerment,” she co-founded a hospital for young mothers and personally raised 15,000 marks to build it. Her sense of service was practical, organized, and deeply human.

Hélène was the kind of woman who didn’t just talk about compassion — she built it, brick by brick.

A Partnership of Purpose

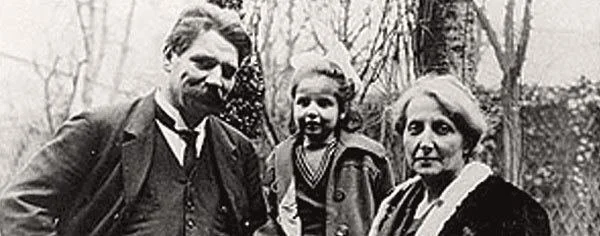

Hélène first met Albert Schweitzer in 1898. He was a young theology student and musician; she was a teacher with an independent mind. They crossed paths again a few years later in Strasbourg, where he was now a pastor and university lecturer.

She admired his brilliance and his quiet rebellion — and when he announced, in 1905, that he would leave everything to serve the poorest in Africa, she didn’t try to stop him.

She joined him.

But first, she prepared. Knowing that he would need medical support, Hélène enrolled in a two-year nursing and anesthesia program in Frankfurt — an extraordinary choice for a woman in her 30s.

When they married in 1912, it wasn’t a romantic fairy tale; it was an alliance of purpose.

The next year, they sailed together to the French colony of Gabon, bound for a mission outpost called Lambaréné.

A Life of Service and Strength

When they arrived, there was no hospital — only dense forest and a poultry shed.

They turned that shed into a clinic.

Hélène organized supplies, cleaned wounds, sterilized instruments, prepared patients for surgery, and trained young African women as nurses. She managed everything: medicines, food, laundry, sanitation, even the relatives who camped outside the huts of their sick loved ones.

In letters home, she rarely complained. When she did, it was never about herself — only about the suffering of those she treated.

People remembered her as disciplined, calm, humorous even under strain, and unwavering in her devotion to the work.

Then came war. While Europe tore itself apart during the First World War, Hélène and Albert fought their own peaceful battle — against disease, poverty, and despair.

But in 1919, at 40 years old, she gave birth to their daughter Rhéna and soon fell gravely ill. What they thought was exhaustion turned out to be tuberculosis. The disease forced her to leave Africa and live mostly apart from Albert for years, though their bond never broke.

From Europe, she wrote, fundraised, and coordinated shipments of medicine. When Hitler rose to power, she fled first to Switzerland, then to the United States with her daughter.

There, she gave public lectures about Lambaréné, raising the funds that kept the hospital running through World War II.

And when peace returned, she did something almost unthinkable for a frail, aging woman with lung disease: she went back to Africa in 1941, traveling across oceans and war zones to see the new hospital that her sacrifices had made possible.

Erased, Then Rediscovered

Hélène died in Zurich in 1957, at the age of 78.

Her ashes were taken to Lambaréné and buried under a tall palm tree beside the spot where Albert had chosen his own grave.

Eight years later, when he died, the world mourned “the Apostle of Peace.”

Newspapers filled their front pages with his name.

Almost none mentioned hers.

For decades, Hélène was reduced to a line: “his faithful collaborator.”

But that line never told the truth.

She was not simply a helper — she was the co-creator of one of the greatest humanitarian projects of the 20th century.

Now, sixty years later, her story is being told again.

In Germany, France, and Switzerland, exhibitions, articles, and documentaries are reclaiming her legacy. Scholars call her a feminist pioneer, a humanitarian leader, and the heart of Lambaréné.

Time, at last, is giving her the recognition she never asked for.

Why She Matters Today

Hélène Bresslau Schweitzer matters because her story mirrors that of so many women who work quietly, faithfully, and brilliantly — only to disappear from history’s spotlight.

She reminds us that real leadership doesn’t always wear medals or titles.

Sometimes, it wears a linen apron and a determined smile.

Her life was about courage, competence, and compassion — the kind that builds rather than conquers.

She shows us that empowerment isn’t about being loud; it’s about being true.

That service can be revolutionary.

And that love, when joined with purpose, can outlast everything — even silence.

Closing Reflection

As I write about Hélène, I imagine her by that river again — sleeves rolled, hands strong, gaze steady.

She didn’t chase glory. She lived her truth.

She believed that healing others was a way to honor life itself.

And in that belief, she changed what it means to be human.

Hélène Bresslau Schweitzer reminds us that compassion is not weakness — it’s a quiet form of courage.

And perhaps, the most powerful kind.

In every woman who serves without fanfare, who builds and holds and heals, a piece of Hélène’s spirit still lives.